It was the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein who said, “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.” As explored by in George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four through the constructed language Newspeak, language not only empowers us to communicate ideas but can also be used to constrain thought. To think and reason is to debate with oneself and how else does one debate ideas but through language? Language is more than communication, it is how we encode, store, and process information. Language is how we think.

Language is more than communication, it is how we encode, store, and process information.

Mathematics has been called the language of science. The empiricism of natural philosophy calls for a language that is simultaneously concise and unambiguous, and mathematics, with its reducible equations and formal proofs, is well-suited to the task. The properties of mathematics have allowed scientists such as the famous Albert Einstein to predict natural phenomenon well before the technology to conduct experiments to verify these predictions were even invented. This once prompted Einstein to ask, “How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?”

It is no surprise, therefore, that the economy has turned to mathematics to make sense of the deluge of data that has resulted from the dawn of the information age. Mathematics provides an unbiased way of representing reality. By applying mathematical thinking to real-life problems, complex cause and effect relationships in the real world can be modeled in simpler yet equavalent terms. This makes the solution easy to arrive at, if not wholly obvious. That is the theory, at least.

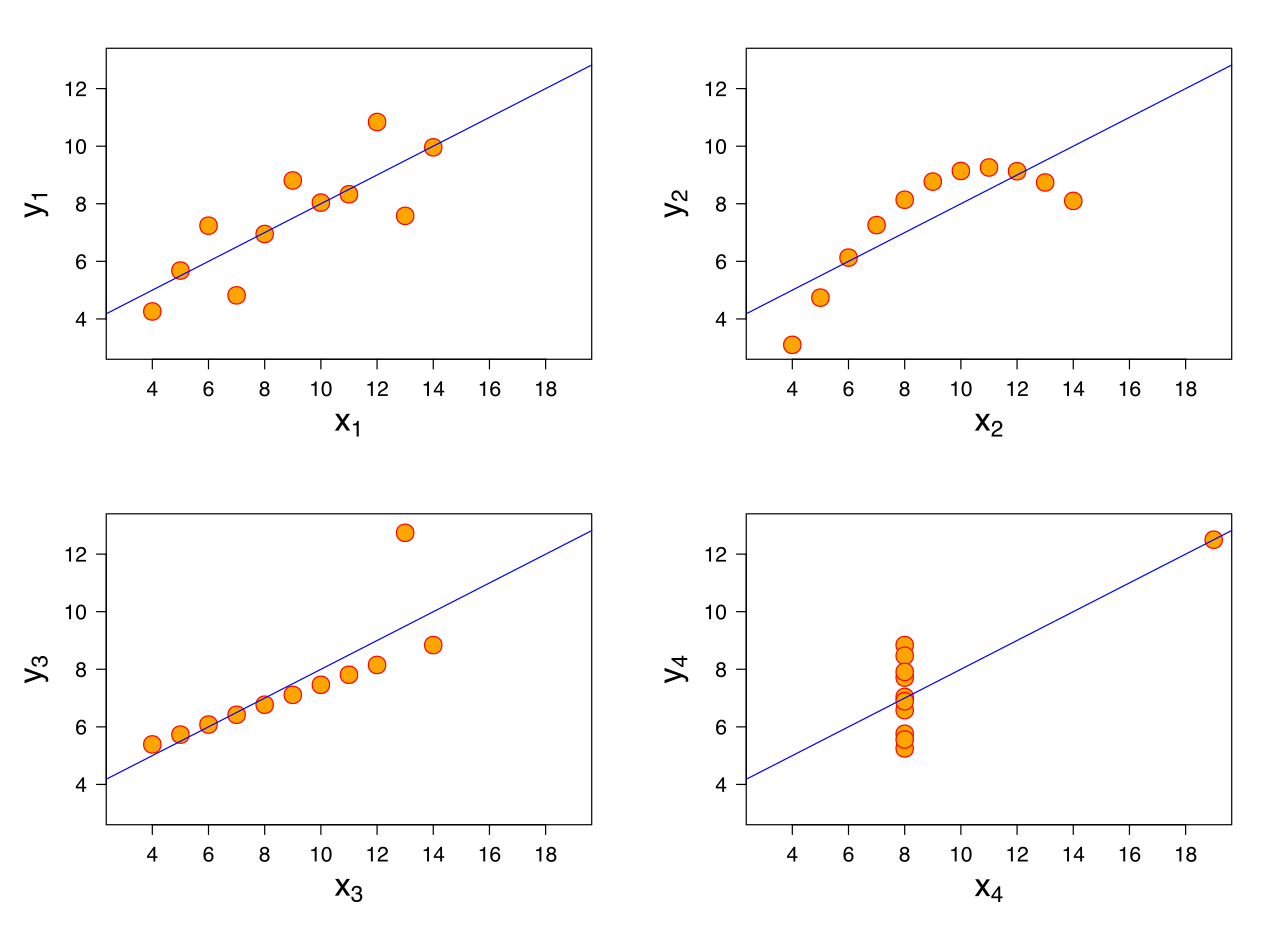

It has been said that there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics. While a little extreme, there is some basis to this assertion. Too often, mathematics has been misused to promote one’s agenda, obscure the truth, or spread outright lies. This is done on purpose by cherrypicking numbers that support one’s claim, but the more common, and arguably more dangerous, case is when this is done unintentionally. Take, for example, the four datasets shown below:

At this point, I want to introduce the concept of correlation. The correlation is a measure of mutual interdependence of factors. A correlation coefficient, the computation of which is detailed here, gives a percentage score of this interdependence where a correlation coefficient of 100% implies that all changes in x coincide with changes in y, and vice versa. If this looks complicated, novices can easily compute the correlation coefficient in Excel, detailed here. All good?

Now, try to solve for the correlation between x and y for each dataset. What do you notice? Next, try solving for the means of x and y.

Not only do the four distinctly different datasets share the almost the same correlations and means of x and y, but the table below shows that even the linear regression equation that estimates the relationship between x and y are also very similar across all four datasets:

| Statistic | Value (Similar) |

|---|---|

| Mean of x | 9 |

| Sample variance of x | 11 |

| Mean of y | 7.5 |

| Sample variance of y | 4.125 |

| Correlation between x and y | 0.816 |

| Linear regression line | y = 3 + 0.5x |

| Coefficient of determination of the linear regression | 0.67 |

These four datasets were constructed by the statistician Francis Anscombe to demonstrate the effect of outliers on statistical properties. While these datasets are purely academic, this is representative of a deeper problem with blind trust in descriptive statistics without a solid background in the underlying numerical theory. In our example, the data was for illustrative purposes only, but imagine what would happen if the data in the charts above were the results of a medical study on the safety of a new drug or an economic report meant to guide national fiscal policy.

A true thing, poorly expressed, is a lie.

Stephen Fry once said, “A true thing, poorly expressed, is a lie.” Mathematics is a language, but like all languages, it rests on us to master the language to avoid making mistakes, because with mathematics, mistakes rarely stay on a spreadsheet but instead form the basis for decisions that affect us all.

The short term solution for most organizations would be to hire a data scientist, and not just any data scientist, but one with solid foundations in mathematics, information technology, and consulting to translate the real life problem to math and retranslate the mathematical solution to real life. The combination of high demand for the data science skillset and lack of supply of qualified employees leads not only to a mad rush for data talent but also overworked data teams.

A more forward-thinking solution would be to increase data literacy within the organization. This approach requires the expertise of a good data scientist even more - the best organizations deserve to learn from the best - but empowers the entire organization. To succeed in creating a data-literate organization, data must be placed front and center with experts given authority to implement positive change within the company. Otherwise, an organization runs the risk of grossly misunderstanding the new mathematical language of business and those mistakes can be costly.

Victor Blancada is a data scientist. Visit his LinkedIn page here.